INTERVIEW WITH PAUL MORRIS from TREASURE ISLAND MEDIA

1: When did you start being a film director?

When I was an impoverished adolescent I stole a cheap movie camera and started asking adults if I could shoot them naked or having sex. I did it because I wanted to watch and the camera gave the sense that I was doing something more than watching. From the beginning whatever “style” I had resulted directly from my negotiation with my own shyness. At first I would stay in a corner, watching from a fixed position. Slowly I learned that I could move closer. Eventually I played with the fact that the sex would change subtlety according to how close I moved, where I pointed the camera. I was–and am–a director only in that I direct the camera toward what I love.

2: How exactly did you start?

I actually started when I was a very young boy. My 16 year old uncle took me to a public pool. Afterward, in the locker room, I watched him strip off his baggy swim trunks. He was wearing an old worn jockstrap underneath and it was wet, threadbare and very full. He watched me as I watched him strip down the wet jockstrap revealing a big uncut cock and heavy low-hanging balls. He slugged me in the head–hard–hoping to snap me out of my little-boy faggot fascination. I went home and drew what I’d seen—more of a desperate little scrawl, really. I eventually worked up the nerve to ask my school friends if I could draw their cocks. The drawings were a ruse, of course: it just made it ok for me to stare at and study their genitals. I’d stare and draw until they got hard, and then I’d suck them off.

Then I got a cheap still camera (this was pre-digital, of course, and I could almost never afford film) and started “photography” at around the age of 8. Then at some point I stole the movie camera and transitioned into being a sex-obsessed 11 or 12 year old.

I can’t remember the exact ages, but these are close.

3: In what city did you shoot your first movie?

The very first one is hard to remember, but most of the first ones were shot in motels in small towns in Southern California. These were all single-reel 8 mm things that never got developed. As often as not there was no film at all. The point was to be in the room with sex.

4: Why did you choose to become an adult movie director?

I didn’t really have a choice. I was a tiny moth circling a big flame.

5: What did you study?

In college, when I went, I studied everything. I loved books nearly as much as I loved men. And music. As a kid I was passionate about classical music. When I was very young–5 or so–I lived for a while with an itinerant fire-and-brimstone preacher named Brother Farrell. He had a one-room shack deep in the backwoods of Arkansas. It was furnished with a bed, a table, two chairs and–astonishingly–a piano. We were alone there, and he taught me to play and read music. He also fucked me a good deal and taught me to enjoy sucking cock as a religious experience. (Many years later I learned that Brother Farrell ended his days in prison because of his love for boys.)

Whenever there was stability in my life I’d work on music. I loved Brahms. I eventually went to college and studied music. I kept dropping in and out of college but eventually got a PhD in music. I’ve always needed music to stay sane.

6: Do you go by your real name or a professional pseudonym? If it is a pseudonym, why are you using it?

When I lived with Brother Farrell, he would call me “little Paul”—he seemed to connect me with the conversion story of Saul/Paul. Although it wasn’t my birth name it’s a name I’ve long answered to. “Morris” I gave to myself when I started doing professional porn. It’s a shortened version of Paul Morrissey whose movies I love.

7: What do you think about pornography?

It becomes more important by the day.

8: Do you work for TIM only?

Yes.

9: Do you have roles other than making the films for TIM?

I’m the resident manic/melancholiac for the San Francisco office.

I do some photography–you can find some of the snapshots I’ve taken online at http://www.flickr.com/photos/paulmorristim/ .

10: How do you come up with your ideas for the films you make?

I hate ideas. Ideas and concepts are bad for porn. Sex is about percepts, specifics, immediacies. Skateboarders speeding down a street–that’s the body thinking in the way a man having sex thinks.

11: Do you do the editing as well?

I teach the editors and then I proof (and re-proof) their work.

The editing is the most challenging part of the entire process of making porn. You edit to maximize the truth of the moment while keeping the story that every sexual encounter has alive. This has become more and more crucial now, since so many men experience porn more than they experience sex. So adhering to the truth is more important than ever.

12: Do you look back to your previous work sometimes?

No.

13: How do you think your film making has changed over the years?

For years I did everything. When I started making money I

would hire people to help with the parts of porn-making I’d grown tired of. Now it’s a team of men. I oversee everything.

14: What characterises your relationship with the actors?

We don’t have actors. They’re men. My relationship with them is that I love them and their sex.

15: How do you choose your actors?

According to the depth of their real sexuality. If they’ve been in much porn I tend to avoid them. The guys who’ve been in a lot of porn become actors.

16: Are the names of the actors real or professional pseudonyms?

For the most part, self-chosen pseudonyms. Though I have trouble with the word ‘pseudonym’. I have everyone who works at TIM in any capacity take a new name. The new name gives you the chance to grow into a new person. You can let go of the habitual persona you grew up with and allow a new identity to grow.

17: If you would analyse TIM movies, which peculiarities do you think they have?

Spontaneity, happiness, crudeness, fun, authenticity.

18: Recently TIM has been expanding its website exponentially. Why?

I don’t know. Matt, my general manager, is responsible for that.

19: Is the income from the web bigger than the purchasing via mail?

Yes.

20: What proportion of TIM income is from its online operation?

I have no idea.

21: Do you monitor what kind of viewers you attract, and if so, how?

I don’t “monitor” them, no. I pay attention to what they tell me. I get lots of comments from lots of men and I take it all very seriously. And there are a number of men who’ve been writing to me since the beginning of the company. They let me know how they think I’m doing, whether the work is on the mark or not. To my way of thinking, I work for them.

22: What kind of public name do you think TIM has?

Strong, scandal-prone, fearless, adventurous, smart, funny, important, enduring.

23: Do you have particular technical approaches that you keep to when you make a movie?

I don’t understand the question.

24: Do you think that what you think is exciting will be exciting for your public too?

I don’t have a public; I have a responsibility to a community and a tradition. Does that sound pompous or overly serious? What I think the people for whom I work find exciting is the continuity of a real and ages old lineage of practice: we’re a living archive of male sexual practice. What’s exciting about watching our porn—when it’s good and it works—is remembering, recognizing and reliving.

25: What do you think is exciting in your movies?

What I find exciting about our porn is the recognition of something real and almost forgotten. A moment, a gesture, a connection. Often, when I’m reviewing a new piece with my guys, I’ll find myself saying “There it is” when some very particular thing happens. It’s never predictable which is why it’s so valuable. Most commercial pornographers seem to believe that formulaic repetition is enough, or that providing some fetishistic storyline or detail will work. That’s why so much porn is closer to death than sex. They give you the skeleton but don’t bother with the flesh. Our work is to try to understand and capture what the flesh is saying.

26: What do you think makes your work different from other porn producers?

One fairly important thing is that our process is painstaking. Also, my personal sexual history is the most far-ranging of any man I’ve met. It’s been my life and I put it all into the work.

27: What do you think makes your work different from the work of your fellow TIM directors?

If you mean Max and Liam, they’re younger and smarter than I am.

They’re much better at the whole thing than I’ll ever be.

28: Do you think you are experimental in your work?

If we weren’t experimental every step of the way, I’d quit. Experiment means risk, risk means surprise, and surprise is life.

29: How do you think your work will evolve?

Male sex in the West has reached a crossroads. Within five years what we now think of as sexuality will be as antiquated and unfamiliar as the rotary telephone or the telegraph. This is currently most clearly being signaled by the unprecedented omnipresence of male nudity. The West is flooding itself—glutting really—with images of nude males and cock. It’s like watching a starving child at a banquet. The effect will be a neutralization of the panic and fear that the culture previously experienced around the idea of the phallus. So the now nearly universal presence of male frontal nudity and arousal is acting as a kind of aqua regia that’s helping to dissolving ossified fields of meaning such as heterosexual, homosexual, marriage, masturbation, pornography and so on. Male nudity obviously isn’t the only element in this massive shift, but it’s one that’s extremely easy to observe.

As in all transitional periods involving cultural and semiotic chaos, everything is volatile and is being reduced to the smallest stable units possible. Still images and repeating gifs are extremely important right now. The gifs in particular freeze sexual time and enable the close study of a particular gesture, an isolated but charged moment. This is paralleled, I think, in the rise in popularity of dance music, a musical genre that’s built around what’s basically a mono-beat, another form of stopped time for the dancing body. We dance to music exactly in the way we masturbate to sexual images, so it’s always valuable to compare contemporaneous porn and dance music.

I’m watching all of this very carefully, spending much of my time monitoring socio-sexual practice, watching what men are doing with their bodies(physical modifications as well as gender practice), with their sex, studying how they present and represent themselves in the various media. So the immediate future of my own work will be to try my best to provide images and practices in my videos and photos that effort toward remembering what’s essential—and there are basic practices and presences that are essential, that have been with men for as long as men have been human—while doing my best to recognize and represent the new worlds of sexual reality as they come into focus.

30: What would you like to shoot that you can’t at present?

The reality of sexuality of males under the age of 18. The longer the culture refuses to embrace the sexual worlds of boys and teenage men, the more stultified and neurotic things will become. A man can’t be a man unless he understands and relates to childhood and adolescence. Our understanding of children today is almost pure kitsch. At this point, the cultural panic surrounding a strange faux-holiness of childhood “innocence” seems to be reaching an hysterical peak. This is paralleled in the artificial and non-nourishing preciousness of gay imagery in the mainstream media (e.g. Glee) and, of course, the mania among gay men surrounding the notion of marriage. Marriage for gay men has little to do with gay identity and sex and much to do with the notion that gay parents are safe for children, good to raise and protect children. I think Reich was right in The Mass Psychology of Fascism in that the repression of sexual truth–in this case the reality of the sexuality and sexual practice and needs of adolescents and children–is a causative element of kitsch and fascism, both of which have been growing in gay culture, particularly in the US.

31: What do you think the greatest challenges are for people making adult movies?

I don’t know.

32: Do you think pornography influences social behaviours?

Yes, although I think considering pornography to be ‘educational’ in the old-fashioned Western sense is extremely dangerous. It oversimplifies and reduces the functional importance of the genre. Pornography is a very sensitive and very complex barometer.

33: Do you think watching adult movies is psychologically dangerous?

No. Pornography is one of the culture’s efforts to cure itself of its own fears, neuroses and violence.

34: Do you watch pornography?

I am pornography.

35: What’s the relationship between TIM and the law?

I don’t understand the question.

36: Have you ever had problems with the law because of your work?

Yes. Oh, I see what you mean. Here’s the crux of a recent interesting run-in with the law: As you know, much of the sex we work with centers around the primacy of a love of semen. The men in our videos love semen, often live to give or take loads. Their sexual identities are based in this. But there are complicated laws in California that are meant to protect industrial workers from exposure in the work place to potentially toxic bodily fluids. Which means that according to law everyone involved in any porn shoot in California must wear protective goggles, gloves, lab coats and so on. Any kind of contact by a person on a porn set with semen, blood or saliva is illegal. This is obviously meant to keep workers safe from, among other things, hiv.

But the men with whom we work are for the most part poz, and taking loads from other men is the basis of their sex. We were recently fined $17,000 dollars by the State of California for allowing bodily fluid contact on a shoot. For the participants in the shoot, however, the sex was actually quite restrained compared to their ordinary sex.

The conflict as I see it isn’t between TIM and the state, it’s a conflict between a sexual culture and the state.

37: With your movies do you think you are giving your public something new, and then to generate a need in the watchers, or do you aim to satisfy an existing need by making what people want?

The word ‘want’ is good. Originally, I believe, it meant to not have something. ‘For want of a horse the kingdom was lost’ and so on. For a lot of people pornography depicts what they desire because they ‘want’ it and they want it because they are afraid of it. Recently a US minor gay celebrity named Tim Gunn publicly admitted that he hadn’t had sex for 29 years. This was obviously out of fear of hiv. This fear, probably the central factor in the gay world for the last 30 years, is one of the many reasons men watch and need gay porn.

38: What kind of feedback does TIM get from the public?

Passionately positive, violently negative.

39: Do you think TIM is different from other studios?

If it weren’t I’d quit.

40: How do you think TIM is different from other studios?

That would require a book to answer.

41: Are your methods of choosing actors changing?

No. I’ve always looked for the same things in men.

42: Do you allow your actors to use drugs during the shooting?

Sometimes, yes. Personally, in my life I’ve experimented with nearly every drug that exists. What I’ve learned is that in themselves drugs never make the sex better. Remember: sex is literally the most primal element of our being. When we engage in real sex, we access aspects of ourselves that date back not thousands but millions of years. Our sex is a direct link to the process that created the species and if you approach it seriously and patiently, that depth can be accessed using nothing more than your maleness.

But the world we live in is noisy and confusing and repressed and afraid. And most men don’t have the luxury of great expanses of time to devote to the exploration of sexual realities. So they plug in to a drug and hope for the best. Sometimes the results can be good and can help to awaken your sexual awareness.

Pragmatically, if a man uses drugs during his everyday sex, he’s welcome to use those drugs in a scene so long as everyone else in the scene is aware of it and completely ok with it.

43: (If so) do you think drugs help the actors to give a better performance?

A performance is something a dancer or an actor does on stage. As much as possible I try to keep the element of performance out of what we do. If a man needs to smoke some pot in order to have more fun and be less nervous, I’m fine with that.

44: Why did you go for bareback movies?

I love what I love. Also, porn as a genre is the antithesis of horror in that the latter teaches that fear is always justified. Porn teaches that fear is only useful if it’s fun.

45: Do you think TIM pays their actors enough?

It’s a complex question. It’s generally accepted by porn producers that if, in his first interview, a man asks how much you pay you show him the door. Among men who aspire to be pros there’s an all too common counterproductive cycle: they equate the sex with money, the sex becomes a job, the sex gets more and more formulaic and performed. That’s why I pay guys with porn experience less.

What’s funny is that I love the commixture of sex and money. In my teens and 20s I hustled to make ends meet. And I love paying for sex now. So paying men to have sex on camera is very natural and a very satisfying process for me. But since the videos we make aren’t just for me, it’s a more complex process. The men have to love sex inordinately. If they live for sex I’ll give them all the money in the world. If they live for money I show them the door.

46: Have you ever rejected an actor because they were too young?

Yes, but only for legal reasons.

47: What do you think is sexy in a man?

Watch yourself sucking cock in Liam’s video. There it is.

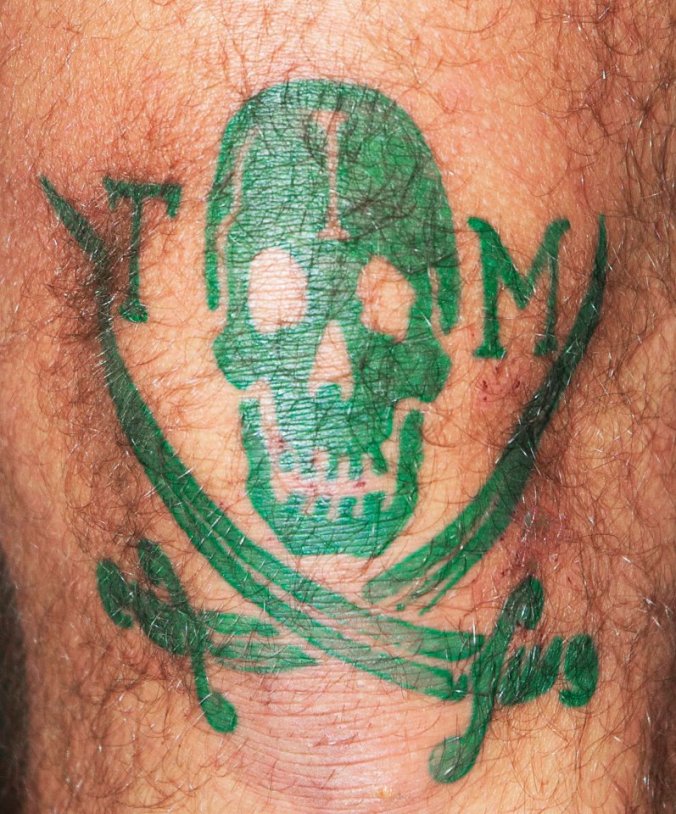

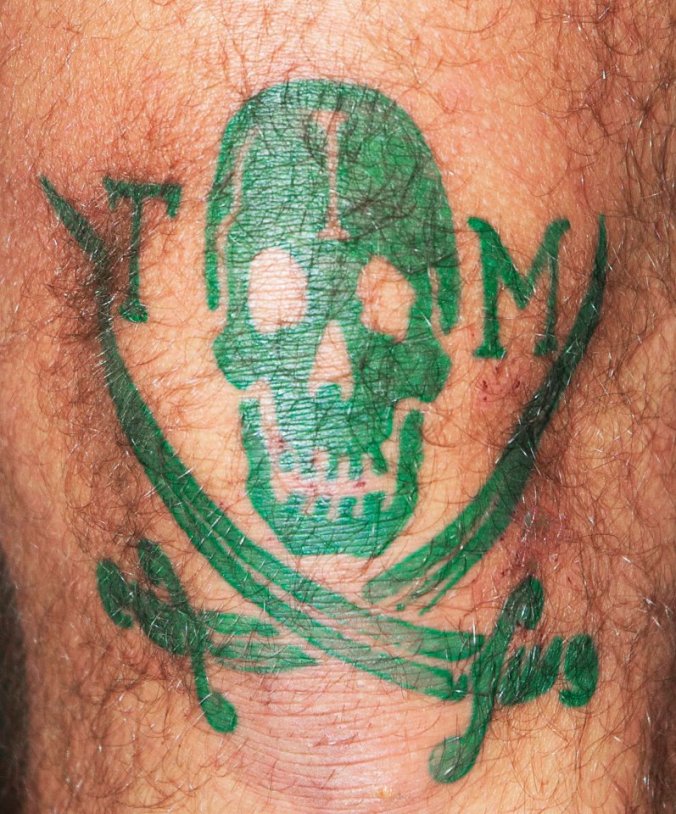

Watch yourself getting tattooed. There it is.

48: Do you choose the clothing for your actors?

No.

49: Do you choose the the way your actors are styled?

No.

50: How important are the spoken words and texts in your movies?

If they’re spontaneous, they’re as important as any other aspect of sex. That’s why I use subtitles. In our office you’ll often find us huddled around a monitor playing a video segment over and over trying to decipher what exactly is guy is muttering under his breath. Then we subtitle it. It’s crucial information.

51: You use actors of various body type. Why?

A man’s body is an expressive vehicle for his sexual persona. I love men of all kinds, but I’m truly passionate about the deep and complex sexual personae.

INTERVIEW WITH LIAM COLE from TREASURE ISLAND MEDIA

1: When did you start being a film director?

I made videos of my friends when I was a teenager. I started making porn in 2008.

2: How exactly did you start?

I made a video of my (then) boyfriend having a wank. Paul Morris liked it, and encouraged me to make more.

3: In what city did you shoot your first movie?

London.

4: Why did you choose to become an adult movie director?

I wanted an interesting experience.

5: What did you study?

Art and music.

6: Do you go by your real name or a professional pseudonym? If it is a pseudonym, why are you using it?

My family name is unusual. I use a pseudonym so I can feel free to make whatever kind of video I want without implicating my family. Liam isn’t the name on my birth certificate, but it’s what everyone in my life calls me, except family and old school friends.

7: What do you think about pornography?

A lot of things, many of them contradictory.

8: Do you work for TIM only?

Yes, so far all my porn is produced and released with TIM.

9: Do you have roles other than making the films for TIM?

Sometimes I draw things, like the dick man or the Suck Dick Save the World logo. I made the animation which opens most TIM dvds since 2009. Some of the music I make has made its way into TIM productions. A song called “Spanish Pork” is on the soundtrack of Island, and another one called “Economy” is on the end credits of one of Max Sohl’s videos, I think.

10: How do you come up with your ideas for the films you make?

My videos are not very idea driven. Whatever ideas are in there come from what the men I film are into.

11: Do you do the editing as well?

Sometimes, but not always. Some scenes in my videos are edited by the TIM editors in San Francisco, including Damon Dogg.

12: Do you look back to your previous work sometimes?

Almost never. Sometimes I see them playing at other people’s sex parties.

13: How do you think your film making has changed over the years?

I used to specify who would be top and who would be bottom at the beginning of a shoot. Now, if there are versatile guys involved then I tell them they can all fuck in whatever roles they feel like. I also used to ask the guys not to get high when we’re shooting, but now I’m fine with them doing that, as long as it enhances the sex. I don’t bring lighting kit to shoots anymore.

14: What characterises your relationship with the actors?

Friendly, casual. I’m always excited and grateful to them that they’re letting me film them having sex.

15: How do you choose your actors?

I interview a lot of men all the time, and choose the ones who seem to be genuinely into sex, and whom the camera likes. I avoid people who are overly concerned about being a porn “star” or making money.

16: Are the names of the actors real or professional pseudonyms?

Some are professional pseudonyms, some are real names, some are a combination.

17: If you would analyse TIM movies, which peculiarities do you think they have?

Documentary style and unchoreographed spontaneous sex between men.

18: Recently TIM has been expanding its website exponentially. Why?

Because increasingly that’s how customers are sourcing their porn, I’d guess.

19: Is the income from the web bigger than the purchasing via mail?

I’m not sure, but if it isn’t now then I imagine it will be in the future.

20: What proportion of TIM income is from its online operation?

I don’t know.

21: Do you monitor what kind of viewers you attract, and if so, how?

We get feedback online through various social networking sites, and to our blogs and forums. I’m not away of any special method of monitoring or profiling our viewers.

22: What kind of public name do you think TIM has?

A varied one. Different people seem to see the company in very different ways.

23: Do you have particular technical approaches that you keep to when you make a movie?

I don’t use additional lighting. Whatever light there is has to suffice.

24: Do you think that what you think is exciting will be exciting for your public too?

Generally, but I’m often surprised by which scenes become the favourites.

25: What do you think is exciting in your movies?

The sense that they are documenting a way of life. Short moments of conversation between the guys can capture a lot about how they live and how the sex they have fits into their lives.

26: What do you think makes your work different from other porn producers?

I watch very little other professional pornography. What I see generally looks more stylised and theatrical than my videos. Some home-made amateur porn reminds me of my own videos.

27: What do you think makes your work different from the work of your fellow TIM directors?

The relationship between me and the men I’m filming is different. Often you can hear me talking to them while they’re fucking. Sometimes you can see me with my camera. My videos are more like home movies than Paul Morris’ or Max Sohl’s.

28: Do you think you are experimental in your work?

I try to be, but not as often as I should. Sometimes it’s fun to just enjoy filming great sex, without trying to re-invent the process.

29: How do you think your work will evolve?

I don’t know. If it evolves at all, I’ll be pleased.

30: What would you like to shoot that you can’t at present?

I’m looking for somebody with a very tame horse. I’d like to film sex between men and horses, because horse cocks are beautiful. So I need a horse-owner who can help me out with that, preferably in a country where it’s legal to do it, shoot it, and release it.

31: What do you think the greatest challenges are for people making adult movies?

The challenge is to create situations that allow the possibility for great sex to happen. Casting is difficult.

32: Do you think pornography influences social behaviours?

Yes.

33: Do you think watching adult movies is psychologically dangerous?

That depends on who’s watching and which adult movies.

34: Do you watch pornography?

Sometimes, but not often. I look at pornographic photos more often than I watch videos.

35: What’s the relationship between TIM and the law?

I believe the company’s main offices in San Francisco make fairly regular use of a legal team.

36: Have you ever had problems with the law because of your work?

No.

37: With your movies do you think you are giving your public something new, and then to generate a need in the watchers, or do you aim to satisfy an existing need by making what people want?

I don’t know. Either theory would be almost impossible to test.

38: What kind of feedback does TIM get from the public?

The direct feedback is mostly very positive. Occasionally we get negative feedback from more remote sources. There are still many people who disapprove of porn that shows unprotected sex.

39: Do you think TIM is different from other studios?

That’s what I hear.

40: How do you think TIM is different from other studios?

I’m not familiar enough with any other studios to make a comparison.

41: Are your methods of choosing actors changing?

They’re not changing, but since moving into London I’ve had more time to interview men. I’m interviewing more new applicants than ever.

42: Do you allow your actors to use drugs during the shooting?

Recently, yes.

43: (If so) do you think drugs help the actors to give a better performance?

I wouldn’t use the word “performance”. Some times the drugs enhance the sexual experience, and that shows in the video. Other times drugs create good feelings, but hinder the body’s basic sexual functions, which is not very exciting to watch. So far, I’ve had mostly very good results.

44: Why did you go for bareback movies?

Because I find bareback sex more exciting to watch.

45: Do you think TIM pays their actors enough?

Yes.

46: Have you ever rejected an actor because they were too young?

I’ve had applications from guys who not old enough for me to legally shoot with them. I tell them to come back when they turn 18.

47: What do you think is sexy in a man?

Intelligence, empathy, cheerfulness, and an appetite for fun.

48: Do you choose the clothing for your actors?

No.

49: Do you choose the the way your actors are styled?

No.

50: How important are the spoken words and texts in your movies?

There are no scripts. Whatever conversation happens in the videos is spontaneous. The parts that I keep in the video are chosen because of what they reveal about the situation and the men speaking.

51: You use actors of various body type. Why?

Because there is not one particular body type that I prioritise when I’m casting. Sex appeal comes in many different forms.